Summers, True Read online

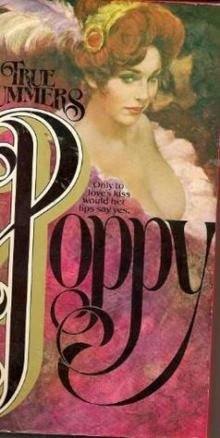

True Summers - Poppy

Gambling Rogues,

The Rush for Gold,

And a Woman Whose

Price was Beyond Passion!

She was the daughter of an English king. From London and Paris where she lived the glittering life of a demimondaine, mistress to Dexter Roark, darkly handsome and mysterious international financier, to the storm-tossed nights of her passage round Cape Horn, and finally to the American land where gold dust sparkled amid the rough-hewn longings of men taming our las frontier in California-Poppy could not forget her past ... and the man whose embrace tore her passion loose and held it gently.

To V.J.H.

With Gratitude for Faith, Hope, and Charity

POPPY is an original publication of Avon Books. This work has never before appeared in book form.

AVON BOOKS A division of The Hearst Corporation 959 Eighth Avenue New York, New York 10019

Copyright

© 1978 by Hope Campbell Published by arrangement with the author.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 78-58891ISBN: 0-380-39446-4

All rights reserved, which includes the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Lurton Blassingame, 60 East 42 Street, New York, New York 10017

First Avon Printing, August, 1978

AVON TRADEMARK REG. U.S. PAT. OFF. AND IN OTHER COUNTRIES, MARCA REGISTRADA, HECHO BN U.S.A.

Printed in the U.S.A.

Prologue

London 1833

SHE was born impetuous and with no regard for rank or propriety. At her first public appearance two weeks after the birth, she dribbled on the royal waistcoat and batted the regal nose with a clenched fist.

Though a fond father many times over, William set her beside her mother on the gold brocade chaise longue. He had ten other acknowledged bastards, but this was his young mistress's child, and the girl looked more beautiful than ever, with her violet eyes shining and her golden hair tumbling down around a bosom more luminously white than the creamy satin of her peignoir.

"I thought I'd name her Violet," Daisy Smith said, handing the baby to the wet nurse.

"Violet? She's red as a beet."

"That's usual."

"Look at that hair."

"I suppose there's Poppy."

"Suitable," William said. "Suitable."

The next day the rubies, in a velvet case tactfully unmarked by his crest, were delivered by a gentleman in black, his livery discreetly plain, to the small cottage on Pallminster Lane. Their disappearance from the royal treasure chests caused such criticism at a politically crucial time, that William dared make no settlement on the baby, let alone ennoble her as he had his other children. He was King of England, but the treasury was low, and in a last flare-up of his Stuart blood to prove he could rule supreme, he began to realize he had overreached himself. Though he had formed a ministry around Sir Robert Peel, the Parliament was determined to teach him that his powers were limited.

He made promises to Daisy for the future. The child would need a large dowry to make anything like an appropriate marriage. The bluff sailor king meant his promises.

He was fond of the child and liked to watch her splashing in her bath. He laughed as heartily as she when the nursemaid was drenched. Later, when she could toddle, her habit of darting from behind doors and wrapping herself around his ankles was taken beamingly as affection. He was much too solid on his feet to trip and fall with a satisfying thud as the butcher's boy and the scullery maid did. She was a mischief, he admitted, but high spirits did a beautiful girl no harm, and her wide-set, amethyst eyes were exceptional. She should do well on the marriage market, for Daisy had a practical head on her lovely shoulders, and could guide her.

Still, the King was not a young man, and this surprising proof of virility in his old age may have given him a false sense of immortality. The political battles were wearing, though the people did not lose their affection for the sailor king, and the defeats made him cautious. He procrastinated, and the general debility that killed him struck before Poppy's dowry was arranged.

Because all his children were illegitimate, his niece Victoria became Queen. Poppy was left the nameless bastard of a beautiful demimondaine without a protector.

Part One

England

April-September 1851

Chapter One

THE Crystal Palace, a blazing arc of glass rising like a fountain from the green turf of the park, shimmered in the late April sunlight. Outside, great dray horses hauled wagons heaped with bales and packing cases of exhibition materials yet to be arranged. The opening was only two days away, and sweating laborers unloaded the cases outside the doors while bearded, frock-coated bobbies patrolled to keep order.

Standing on tiptoe among the pushing crowd, as close as the bobbies would let anyone get, Poppy Smith tried to see through the glass. Painters still were working inside, and red carpets hung from the girders. She was sure the elm trees in there had grown in the last two weeks, enormous trees right inside the building and beautiful now that the birds were no longer perching in them and making a nuisance on everything around. The Duke of Wellington had solved that for the Queen as he had solved so many worries. "Try sparrow hawks, ma'am," he had said.

Poppy drew a long, ecstatic breath. The Great Exhibition was going to be the most wonderful thing that had ever happened in London or even all England. Paxton, who had grown the giant lily in a glass house for the Duke of Devonshire, and Albert the Good, the Prince Consort, had raised this shining pavilion. It was almost 'as if they had waved a wand over the park this winter, and it had sprung up like a fairy arcade of bright streets and sunlit spaces. Now all the countries of the world were sending their most advanced and best products. Everything a manufactory could make or hands could fashion would be on display inside the Palace.

Poppy jabbed an elbow into the side of the fat woman who was trying to push her off the little mound on which she stood. She anchored herself more firmly by digging into the turf the small green parasol that matched the stripe of her plaid street attire.

Then she felt the empty space beside her and turned uneasily, amethyst eyes narrowing as she looked around. Andy had slipped away, and she knew what he was trying to do. He was determined to get inside, and if the bobbies caught and held him, as they surely would, they both would be in terrible trouble. When Daisy had given them their season tickets, she had said they must never come here without telling her. They had not told her. Worse, when the Reverend Dr. Minton, who had been their tutor these last two years, had dozed off after morning tea, for he was elderly and often weary from reading late into the night, they had slipped out of his rooms and run away without a word to anyone. Andy detested Julius Caesar, Poppy abhorred mathematics, and the Exhibition beckoned.

"My brother," Poppy murmured.

"That way," the fat woman said, pointing toward the Palace, and pushed triumphantly up on the mound.

Poppy debated shoving back, as any right-thinking Londoner was obligated to do, and then shouldered and wriggled her way through the crowd to the front. She would not have been surprised to see Andy right under the hoofs of the dray horses or hiding behind one of the bales, waiting his chance to slip up to the doors, but she could not see his halo of golden curls anywhere.

She looked toward the small hill where pickpockets were supposed to congregate, but even Andy would have better sense than to go there. Then, in a small group of trees to her right, she caught a glint of gold as high as a man's elbow. Edging along in front of the crowd, murmuring apologies, she rehearsed a tirade and discarded it. Instead she would threaten not to help him with his lessons for a week. That would keep him docile.

At the edge of the trees, she stopped, sti

ffening. Andy was talking, his deceptively angelic face tilted up, to a big man. Poppy did not like the man's looks. She did not like his full, damp underlip or his moist, protruding eyes. She did not like his fancy embroidered waist-coat and ruffled shirt-they were not only old-fashioned but in bad taste. Especially she did not like the way his plump, ringed hand was fondling Andy's shoulder.

Poppy had heard about such men from Daisy. Daisy had grown up in the country, during the frank Georgian era, and she could be a blunt-spoken woman. She had warned them both. Andy was a fool.

Poppy did not run, but she quickly arrived beside them with a busy rustle of her underskirts. "Andy, we've got to go. Come on."

He raised limpid blue eyes. "We can't go home yet, or Daisy will know we slipped away from The Rev."

How much had he told the man? At the least that they were unchaperoned and would not be missed for hours. "It's hot. I want to find a water ice seller," she said.

"So you're the sister, miss?" The man's voice was unpleasantly soft. "I was just telling the young man that I have a marvelous toy train I'd like him to see. I live just over there. You can come with us."

"No. No. Andy, come on."

"I want to see the train."

Poppy felt her face getting red. How could any London boy, eight, almost nine, be so stupid? "No. Come with me. Now."

"You'd enjoy the train, too." The man's hand clamped on her arm like a steel band. "I have a friend I'll ask to join us. I know he'd like to meet you."

Did he think they were going to walk meekly into some locked, shuttered place to be chloroformed and raped? "Let me go," Poppy hissed, digging in her heels.

He had Andy's arm in his other hand. "Come sweetly now. It's just across the road." He jerked her arm up behind her.

She gasped and tried to raise her parasol, but he twisted her arm high, turning her until she bent half double, her face crushed against his waistcoat. She kicked futilely, and he twisted her arm higher. She gulped down nausea, wondering if her arm had been dislocated.

"Sweetly, softly," he whispered. "Quiet now. We'll have a water ice there, and I've some tin soldiers to show the boy, too."

"Trouble?" a deep voice inquired.

"My sister's children up from the country," the man said hastily. "I brought them up for the Exhibition as a treat, but it's spoiled they are, ripe spoiled."

"Not yet. Let them go, Archie. You don't remember me, but I was there when you had that little trouble in Dorset last year."

The man's hand loosened like magic, and he fell back. Poppy staggered against a tree, eyes closed, gasping for breath. A bobby, a bobby had saved them. And caught them too, but that was better than this monster,

"Go play with your tin soldiers, Archie," the deep voice said. "And don't forget again that people know you and your special little tastes."

As Poppy opened her eyes, the plump man turned with a whip of his coattails and scurried off among the trees. Her eyes purple dark, she stared at the stranger who stood leaning indolently on his cane beside Andy. He was not a bobby, and she knew she had never seen him before. She would not have forgotten him. He was -subtly different from anyone she had ever known. He was impeccably dressed in a short, dark-gray coat with lighter gray trousers and a fawn waistcoat. The excellent tailoring almost concealed that his shoulders were too broad and his hips too narrow. The gold head on his cane was just a touch too heavy. His black hair was a shade too short, and his neat sideburns led to the merest thread of a mustache. His skin was bronzed, but it was not the weathered coloring of a hunting man. His face was too lean and strong-jawed to be completely handsome, but everything about him proclaimed a gentleman of wealth and good taste. Yet something about him was not English. Perhaps it was his eyes-of a strange, changing color like the stone they called a cat's-eye.

"Are you here with your mother or an escort?" he asked. Then he read the guilt in their faces. "So you're alone? I'll take you home."

"Please, sir, it's all right. We have our fare for the horsecab," Andy piped up.

"I'll take you home."

Daisy would not be leaving Pallminster Lane for her daily drive in the park for another hour. They dared not return so early. Poppy swallowed hard and said in her sweetest tone, ''We thank you, sir, but our mother does not allow us to ride in a carriage with a strange man." For a moment, the cool eyes looked so hot she thought she had gone too far and he would answer with a scathing reminder of his timely rescue.

Instead he smiled. "Naturally not. I'll put you in a cab and pay the driver and come along behind you."

"You are too kind, sir," Poppy refused.

Andy seemed to have taken one of his inexplicable likings to the stranger. He slipped a hand into his and confided, "We can't go home yet, you see, but we'll be all right."

"So that's the way of it."

Andy nodded, looking up worshipfully. ''You wouldn't happen to know how to get us inside, would you, sir?"

Then it sounded, Daisy's shriek. She worked hard at her genteel manners, though she was not one to worry if people said there was a hint of the vulgar about her. But when she was shocked, she turned pure country woman. Her shriek split the air.

''My children! Andy! Poppy! What are you doing over there?"

Poppy and Andy looked at each other, white faced. Daisy, too, had been unable to resist an impulsive visit to the Exhibition. They consulted silently over what explanation they could give for their presence and knew there was none. They could not say The Rev had let them go early or even that he had dozed off and they had slipped away to spare him. Daisy would ask him, and he would promptly tell her the whole. Twice lately he had wakened after a short time and found them gone. A short walk could have been their excuse when they returned, but they had not returned at all, either day. Even the second time, he had not told Daisy, but he had warned them he was too old and tired to stay to teach pupils who did not wish to learn when he had a son with a country parish who had offered him a home. Now Daisy had caught them, and The Rev would say the third time was too much.

"Oh, he's gone," Andy wailed. "The grand gentleman is gone."

Poppy could not think how he could have slipped away so quickly and quietly, but he was gone. "Thank goodness for that," she said crisply. "Now don't you dare mention him-or that train and toy soldier man, Andy. Don't you dare. At least Daisy can't punish us for something she'll never know."

"Would he have told on us?" Andy cried, disappointed.

"With bells on and fireworks," Poppy swore. She added darkly, "He had a foreign look about him."

Chapter Two

The terrifying thing was that Daisy made no threats. As they had guessed, unable to resist the final bustle before the opening of the Exhibition herself, she had started her drive early. Now she had Peters turn her carriage straight around and take them all home. She sent word by Peters that Mr. Hammett, who had been her gentleman for the last year, was not to call that evening. She told Poppy and Andrew to go to their rooms and stay there. Mrs. Peters would bring them bread and butter and broth on a tray and that was all they were to expect. She left to see the Reverend Dr. Minton.

Sitting in her sewing chair in front of her room's unlit fireplace, Poppy knew she was in the worst trouble of her life. She loved her home, the little cottage on Pallminster Lane. It had three bedrooms upstairs, the parlor and dining room down, and a kitchen that looked out on the small enclosed garden toward the carriage house, which had rooms for Peters and Mrs. Peters above.

She would have enjoyed her lessons with The Rev, but Andy was no scholar. The Rev thought any boy was as bright as a girl twice his age, so he set them the same tasks. Even at the hardest of those in mathematics, she had to hold back so Andy would not seem a dullard and be in trouble.

Looking at her pretty, glazed pink tile fireplace, she thought it would break her heart to leave her home and London. Probably Daisy would try to find boarding schools that would accept them, even if their mother was of a known profession. But she had t

ried before and failed. So the worst that could happen would be a terribly strict tutor who used the cane freely. She would probably take away their season tickets to the Exhibition and their spending money, too. She might even say Poppy was to have no new summer dresses. What worse could she do?

Daisy had always sworn she would never apprentice them. They were too well-bred for any work of that type. They could do better. She thought she might get Andy into the Civil Service when he was old enough, provided she could find the right gentleman to make a strong recommendation. Poppy was to marry. Beauty was better than any dowry, Daisy sniffed, and as to how Poppy was to meet proper young men with honorable intentions, time would take care of that.

Poppy was not so sure. She had no school friends to invite her to small dances to meet their brothers, and Daisy's friends did not have sons who were eligible. The one man who hinted he might make an offer, she had regarded with horror. He was one of Mr. Hammett's friends and nearly as old and much fatter. Daisy said that he had buried two wives and had any number of half-wild children hidden away in some country house and that he was frantic to find somebody to care for them, a woman obligated to stay regardless. Mr. Hammett did not like to be reminded Daisy had two large children on the premises, so he urged the match.

Summers, True

Summers, True